It was the snapshot heard ‘round the world. Eventually.

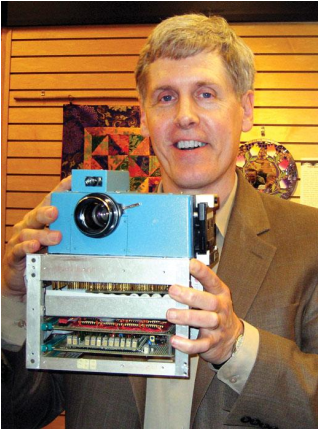

In late 1975, few people were aware that the planet’s first digital camera had been successfully tested—even within Eastman Kodak Company, where Kodak engineer Steven

Sasson spent the better part of a year developing an 8 pound prototype that was the size

of a small toaster (see Figure 1.1). The first photograph taken by this first digital camera in December 1975, was in black-and-white and contained only 10,000 pixels—one

hundredth of a megapixel. Each image took 23 seconds to record, and a similar amount

of time to pop up for review on a television screen. But the age of digital photography

had begun.

Of course, digital cameras of the 1990s were expensive, low-resolution devices suitable

for specialized applications such as quickie snapshots you could send by e-mail or post

on a web page (at the “low”, $1,000 end) to news photographs of breaking events you

could transmit to the editorial staff in minutes (at the stratospheric $30,000 price point).

Then, in 2003 and 2004, Canon and Nikon finally made interchangeable lens digital

SLR cameras affordable with the first Canon EOS Digital Rebel and Nikon D70 models, which cost around $1,000—with lens. Digital SLRs had been available for years—

but now the average photographer could afford to buy one.

Figure 1.1= Steve Sasson invented the digital camera in 1975.

(Photo by Michael D. Sullivan)

This initial chapter provides a summary of where the dSLR is today and how it works.

In later chapters, I’ll show you how to use these tools to raise the bar on image quality

and improve your creative vision. By the time we’re done, you’ll be well on the road to

mastering your digital SLR.

Amazing New Features

Consider the incredible array of new features found in the latest crop of digital SLRs—

and promised for future cameras that are just around the corner. I’ll explain each of these

in more detail later in the book, but, for now, just look at the new capabilities that have

helped make the dSLR the fastest growing segment of the photography market. The list

is long, and can be divided into three segments: improvements in the sensor/sensor

assembly; improvements in the other camera hardware/software components; and

improvements in software used to manipulate the digital images we’ve captured.

Sensor Sensations

I’ll cover each of these breakthroughs in more detail later in this chapter and elsewhere

in this book, but if you want a quick summary of the most important improvements to

the sensor and its components, here’s a quick list:

■ Full frame isn’t just for pros anymore. So-called “full-frame” cameras—those with

24mm × 36mm sensors sized the same as the traditional 35mm film format—are

becoming more common and affordable. Sony already offers a 24.6 megapixel camera body for less than $2,000, and during the life of this book I expect to see similar low-cost full-frame models from Nikon, Canon, and others. Full-frame dSLRs

are also prized for their low noise characteristics, especially at higher ISOs, and the

broader perspective they provide with conventional wide-angle lenses. I’ll cover the

advantages of the full-frame format later in this chapter.

■ Resolution keeps increasing. Vendors keep upping the resolution ante to satisfy

consumers’ perception that more pixels are always better. In practice, of course,

lower resolution cameras often produce superior image quality at higher ISO settings, so the megapixel race has been reined in, to an extent, by the need to provide

higher resolution, improved low-light performance, and extended dynamic range

(the ability to capture detail in inky shadows, bright highlights, and every tone inbetween). The top resolution cameras won’t remain stalled at 25 megapixels for very

long (I expect 32MP to become the new high-end standard), but we’re rapidly seeing all the mid-level and entry-level cameras migrate to 16–21MP sensors. You

won’t see many cameras with less resolution introduced in the future. Of course,

Canon has announced a 120MP 29.2 × 20.2 APS-H (roughly 1.3X “crop” factor—

more on that later), and a humongous 205mm × 205mm sensor that is 40 times

larger than Canon’s largest commercial CMOS sensor. (Actual resolution of this

mega-sensor hasn’t been announced—it will depend on how large the individual

pixels are.)

■ ISO sensitivity skyrocketing. Larger and more sensitive pixels mean improved

performance at high ISO settings. Do you really need ISO 102,400 or ISO

204,800? Certainly, if those ridiculous ratings mean you can get acceptable image

quality at ISO 25,600. For concerts and indoor sports events, I’ve standardized on

ISO 6400, and have very little problem with visual noise. In challenging lighting

conditions, ISO 12,800 isn’t out of the question, and ISO 25,600 (which allows

1/1000th second at f/8 or f/11 in some of the gyms where I shoot) is practical.

■ Professional full HDTV video is possible with a dSLR. The opening title

sequences of Saturday Night Live were shot in HDTV with Canon dSLRs.

Director/cinematographer Ross Hockrow shot his most recent feature film with

those cameras. The HDTV capabilities of the latest dSLRs aren’t just a camcorderreplacement. If you’re a wedding photographer, you can use them to add video coverage to your stills; photojournalists can shoot documentaries; amateur photographers can come home from their vacation with once-in-a-lifetime still photos and

movies that won’t put neighbors to sleep, too.

■ Live View has come of age. Only a few years ago, the ability to preview your images

on an LCD screen was a point-and-shoot feature that most digital SLR users could

see no need for. Today, of course, Live View is an essential part of movie shooting,

but improvements like “face detection” (the camera finds and focuses on the

humans in your image), “subject tracking” (the camera is able to follow focus specific subjects shown on the screen as they move), and zoom in (to improve manual

focusing on the LCD screen) can be invaluable in certain situations. Something as

simple as the ability to focus at any point in the frame (rather than just at the few

fixed focus points marked in the optical viewfinder) can be very helpful.

■ Sensor cleaning that actually works. Every time you change lenses on your dSLR,

you allow dust to enter the camera body and, potentially, make its way past the

shutter and onto the sensor. Every digital SLR introduced in the past few years has

a “shaker” mechanism built into the sensor that does a pretty good job of removing dust and artifacts before it can appear on your photos. You’ll still need to manually clean your sensor from time to time, but the chore can be performed monthly

(or less often), rather than daily or weekly.

■ Image stabilization. Camera movement contributes to blurry photographs.

Optimizing anti-shake compensation by building it into a lens means you have to

pay for image stabilization (IS) in every lens you buy. So, an increasing number of

vendors are building IS into the camera body in the form of a sensor that shifts to

counter camera movement. Unfortunately, “one-size-fits-all” image stabilization

doesn’t work as well with every lens that can be mounted on a camera, but vendors

are learning to adjust the amount/type of in-camera IS for different focal lengths.

■ Marginalia. Other sensor improvements have been talked about, and, in some

cases, even implemented, without generating much excitement. Foveon continues

to improve its “direct image” sensors, with separate red, green, and blue layers that

allow each pixel to detect one of the primary colors. (“Normal” sensors are segmented into an array in which each pixel can detect either red, green, or blue, and

the “missing” information for a given photosite interpolated mathematically.) But,

few people are buying the Sigma cameras that use these sensors. Vendors continue

to improve the tiny “microlenses” so they can focus converging light rays on the

photosites more efficiently. CMOS sensors have more or less replaced their CCD

counterparts, for reasons that nobody cares about anymore. None of these enhancements are as interesting as the others I’ve listed in this section.