I'm a journalist for publications such as The Guardian, Vice, The Diplomat and Narratively and my first book, a memoir, came out just over a year ago [Amazon link]. It's won numerous awards and sold thousands of copies. And now I want to give it away. This is the tenth installment [Prologue | Ch 1 | Ch 2 | Ch 3 | Ch 4 | Ch 5 | Ch 6 | Ch 7 | Ch 8 ] and every few days I'll post another chapter. From the back cover:

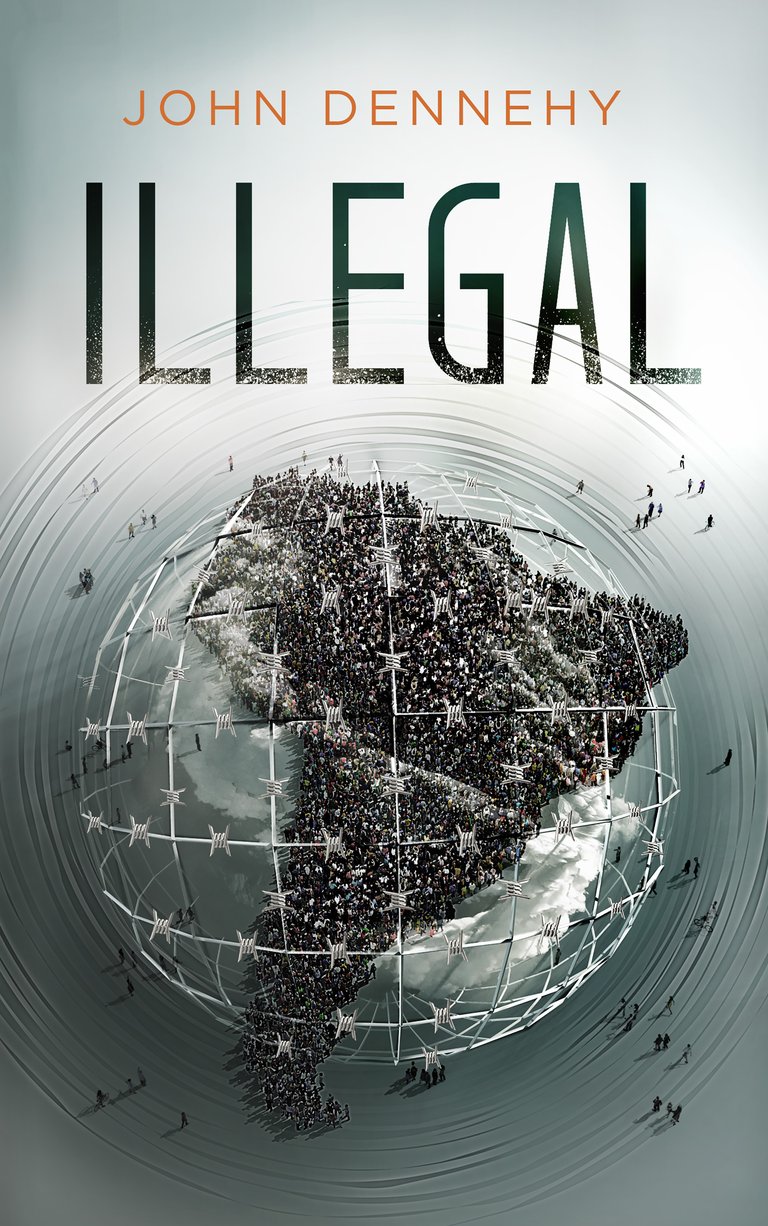

A raw account of a young American abroad grasping for meaning, this pulsating story of violent protests, illegal border crossings and loss of innocence raises questions about the futility of borders and the irresistible power of nationalism.

Behind the Baricades: Love & Revolution (3) [Chapter Nine]

Lining both sides of the highway between us and the blockade stood hundreds of soldiers, their rifles out. They stood in neat rows almost exactly along the white line of the shoulder, leaving the road deserted and creating a pathway. The uniformed men were stiff, their bodies tense; their faces young and scared. The cluster of farmers at the blockade was facing north, toward the capital, toward the soldiers, and toward the caravan of reinforcements we had arrived with.

All around us was farmland. To one side was a massive field of broccoli and on the other side cows munched on grass, oblivious to the looming confrontation. The military held the guns, but this was still the farmer’s territory.

We stepped onto the empty road as the pickup truck that had carried us turned around and drove off. In front of us, past the military, we could see the mass of rebelling farmers clustered in the roadway. Through small breaks in the sea of people we could see the fires burning, and behind that we could barely make out the great mounds of earth that rebels had pushed onto the highway. Black smoke from burning logs and tires and the blue-gray tear gas swirled together above them and melted into the air. There was a breeze blowing toward us, and while we weren’t close enough to be covered in the fog of poisonous colors, the stink of burning rubber filled our nostrils and sat on our tongues. Lingering tear gas scraped against our eyes and lungs. Ana and I each held our fist to our mouth and breathed through crumpled bandanas in our hands, but we still felt it.

The rebel reinforcements lined up in groups. To reach the main blockade they would have to pass directly through the gathered military. It looked like they were about to walk into a massacre, but nothing would stop them from moving forward.

Ana grabbed my arm and pulled me away. She didn’t say a word, but she didn’t have to. The situation was tense and everyone knew that things were about to explode. Ana released my arm as we rushed past the farmers and approached the gauntlet of heavily armed military. I noticed for the first time that she was wearing her black leather boots and somehow, above all the noise, I heard her heels hit the pavement. Her steps were hard and fast. We walked without speaking, the military to our right and left and a mass of rebels to our front and rear, but the road was eerily void of life where we were. Halfway through, I turned around to look at the farmer’s reinforcements.

The new arrivals were still close to the trucks, slowly inching forward, waiting for everyone to group. The people closest to the police began locking their arms together. Ana and I kept our brisk pace once we left the gauntlet of olive green uniforms and high powered assault rifles. We passed through the mass of farmers who had been sleeping on the highway and stopped at the line of fire across the road.

There were not many people around us here because most of the dissidents were now massed at the northern edge of the group, where we had come from. Some children were throwing more branches onto the fire and a few elderly couples were sitting down and resting.

“Tenemos que ir—We have to go,” Ana said.

I looked back at the mass of farmers, and looked at Ana. “But…”

“I want to stay too,” Ana said. “But this is too dangerous for you. You know that.”

We heard a pop and saw a cloud of tear gas rise from the area the soldiers occupied. The crowd roared, and pushed forward, into the gas. I had never seen people run into gas before; I watched, stunned by their will. Then half a dozen more pops exploded at once and the crowd pushed back, running away. The children near us ran to the fight. Most of the graying men and women stayed seated but a few slowly got up and followed the children.

“No van a abrirla—They won’t open the highway. These people will not lose. But we have to go, it’s getting very dangerous now,” Ana said, grabbing my arm a second time. “We have to go,” she said again more forcefully, her face muscles tensing with her words and her eyes betraying her concern for me.

We walked to the side of the highway and onto the gravel and weeds at the shoulder, past the piles of earth and back onto the open highway.

We had spent all day traveling to the blockade and when we finally got there we didn’t know what to do. Our plan to witness with our own eyes, had ended once we stepped off the pickup truck and walked through the gauntlet of soldiers.

When we set off that morning neither of us knew where the blockade was, just that it was north of the city. Even when we were dropped off after our first ride we had no idea how much we had overshot it. It was actually much closer to Latacunga than either of us thought, but I’m still glad the journey took so long. Hitching on the empty highway, placing stones on the miniature blockade and traveling in the farmer’s caravan all connected me to the place in a way I had never felt before. I was still young and naïve but somewhere along the abandoned highway I lost any notion that Ecuador might be temporary for me. When Ana and I hitched the last stretch back to the city, I was going home.

While I was moving south, back to Latacunga, Lucía, unbeknownst to me, was walking north. I still did not have a cell phone, and even if I did, Ecuador only had cell coverage in the city centers, so there was no service at the blockade or the 26 miles between Lucía and I. She had walked most of the day though similar blockades. She was still on the highway when Ana and I returned to Latacunga.

As soon as I reached my rented room I collapsed onto my bed. A few minutes later I heard a knock on my door. Lucía’s hair was matted down with sweat and her clothes were caked in a layer of fine dust. But she was beaming, wearing an incredible smile and a bulging backpack on her shoulder. She burst through the entryway and wrapped her arms around me before I even had a chance to speak.

“This might last a long time—and I couldn’t wait to see you,” she said. She had walked the last three miles alone, and through a city under siege.

There was nothing I wanted more. That day, laying exhausted on my bed with Lucía at my side, both of us reeking of sweat and fire, I decided to take a cue from the farmers and make Lucía the lopsided battle I would refuse to give up on. Lucía became a sort of personal revolution for me. She had come to represent the promise of a better tomorrow that I had become so infatuated with. We had our differences and she had lied to me about her own history when we began, but we loved each other, and if we could make it to each other that day, then why not every other one to come.

In the following months Lucía and I grew ever closer. Then, late in the spring of 2006 she came to my door with that same look of self-pity, and shattered my reality for the second time. We walked into my room and sat down next to each other on the bed.

“You’re going to hate me,” she said.

“No, I won’t. You know that I love you. You know that you can tell me anything and I will still love you.”

“Promise?”

“Yes, always and forever.”

“I’ve been married the whole time. We married before my son was even born. Since the first day I met you I have been married.” She paused and her tone changed from sadness to desperation. She spoke quickly. “I never believed I could change anything until I met you. You’re the one I want to be with.” Almost as an afterthought, she added, “I’m getting a divorce.”

I didn’t respond. I didn’t make a noise nor move a muscle. Lucía put her head on my lap and wrapped one arm over my legs, as if she was hugging them. I just stared forward. My Spanish had improved and I was sure I understood her words correctly, but it took me a long time to react to them.

Lucía was crying in my lap and her sobs were getting louder. I realized I was crying too. I looked down and saw that my hand had moved onto her back. When Lucía sat up she looked me in the eye and held my gaze as she fell back onto the bed and laid down next to me. She put her arm out and I laid down on top of it. We held each other tight. Water continued to streak down my cheeks and Lucía sobbed on and off.

“He violated me, but I want that to be my past. I want a better future. I want to be with you.”

And I still loved her. It’s not easy to explain or rationalize now, but I still loved her. I still wanted to be next to her. All of my anger went to a faceless man in a military uniform, and all of my heart went to helping Lucía break from her past.

--

for those interested in where we are, here is the Table of Contents

You got a 9.51% upvote from @booster courtesy of @johndennehy!

NEW FEATURE:

Quick Delegation: 1000| 2500 | 5000 | 10000 | 20000 | 50000You can earn a passive income from our service by delegating your stake in SteemPower to @booster. We'll be sharing 100% Liquid tokens automatically between all our delegators every time a wallet has accumulated 1K STEEM or SBD.

Hi @johndennehy!

Your UA account score is currently 1.595 which ranks you at #33511 across all Steem accounts.

Your rank has dropped 7687 places in the last three days (old rank 25824).Your post was upvoted by @steem-ua, new Steem dApp, using UserAuthority for algorithmic post curation!

In our last Algorithmic Curation Round, consisting of 227 contributions, your post is ranked at #210.

Evaluation of your UA score:

Feel free to join our @steem-ua Discord server