From Judas Iscariot, who betrayed Jesus for 30 pieces of silver, to Bernard L. Madoff to the standard member of Congress fighting tirelessly to further the interests of campaign donors, human history is full of examples of money’s ability to weaken even the firmest ethical backbone.

Money sows mistrust. It ends friendships. Experiments have found that it encourages us to lie and cheat. As Karl Marx, the scourge of capitalism, noted, ‘‘Money then appears as the enemy of man and social bonds that pretend to self-subsistence.’’

Yet though we clearly understand money’s power to debase character, we have less certain a grasp on what it is about money that corrupts us so. Is it simply greed? Does the appetite for the more comfortable life that money can buy push us over the line?

A new study by researchers in organizational behavior from Harvard University and the University of Utah suggests an entirely different dynamic: the simple idea of money changes the way we think – weakening every other social bond.

The researchers performed a suite of experiments on several hundred undergraduates. First they exposed some to phrases like “she spends money liberally” or pictures that would make them think of money, and others to images and phrases that had nothing to do with the stuff.

Then they made them answer questions to flesh out whether their morals would flag in the presence of temptation, and how they articulated the behavior to themselves.

Sure enough, students who had been primed to think of money consistently exhibited weaker ethics. More interestingly, perhaps, they also framed their choices as products of cost-benefit analysis. In other words, they stepped out of morality

For instance, they were more likely to answer that they would filch a ream of paper from the university’s copying room. They were more likely to lie for a financial gain and explain it to themselves as “primarily a business decision.”

“Social relations, which we assume are the fundamental basis of morality, can become de-emphasized so that moral considerations are obscured,” the researchers wrote. “A cost-benefit analysis ensues which focuses on the self to the exclusion of others.”

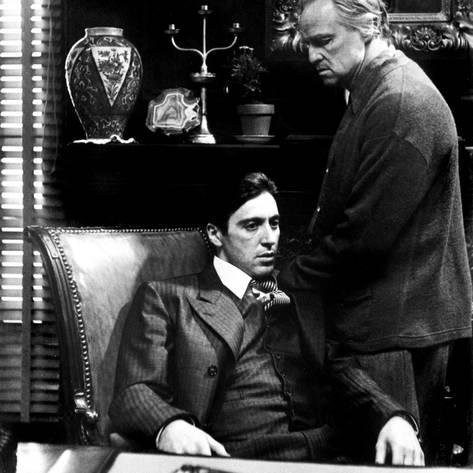

Money, in other words, puts us in the frame of mind of Michael Corleone as he decides to enter the family business. “It’s not personal,” he tells his brother. “”It’s strictly business.”

Hi! I am a robot. I just upvoted you! I found similar content that readers might be interested in:

https://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/06/13/how-money-affects-morality/

@originalworks