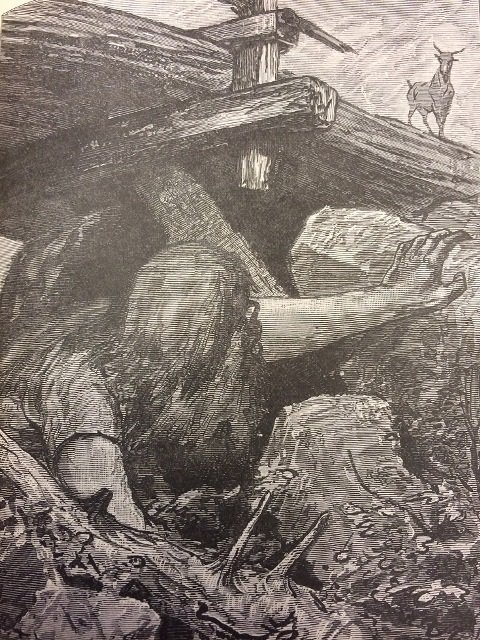

The word "troll" entered mainstream English in 1859 with the translation of a collection of Norwegian folktales published by Sir George Webbe Dasent (1817-1896). His "Popular Tales from the Norse" included the popular story of “The Three Billy-Goats Gruff.” The monstrous troll under the bridge waiting to eat innocent goats provided a vivid image for all who heard the tale as children. Since the publication of that book, the troll gained a firm foothold in his new British and North American homes.

Norwegian composer Edvard Grieg (1843-1907) brought trolls to center stage again with the 1876 premier of his Peer Gynt Suites, a musical accompaniment to a Henrik Ibsen play. Peer Gynt’s rush through underground passages, in the rousing “In the Hall of the Mountain King,” gave the world a musical portrait of trolls in what is now one of the more famous compositions of all time. Grieg’s popular work found English-speaking listeners already aware of the dangerous realm of the trolls. But it had been less than twenty years since the monstrous creature first crept into North American and British culture.

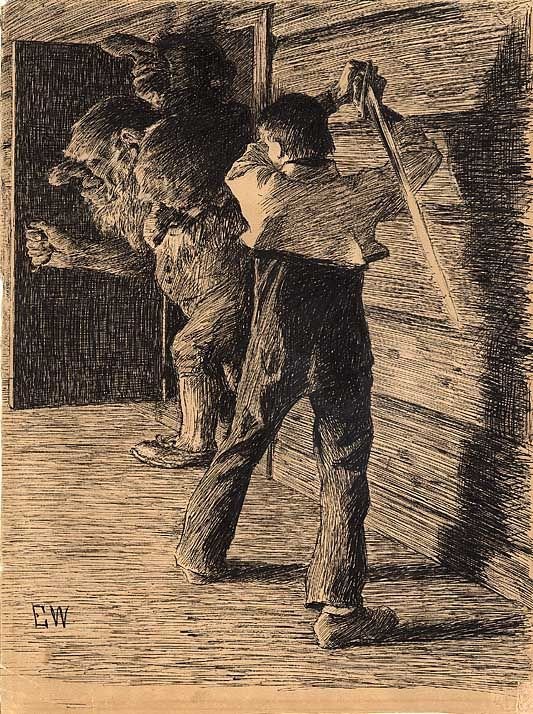

J. R. R. Tolkien introduced the world to his trolls with The Hobbit, published in 1937. Seventeen years later, his 1954 epic bestseller, The Lord of the Rings, referred to the creatures again. Tolkien’s trolls were large, grotesque, stupid, and very dangerous. J. K. Rowling used a troll in her premiere novel, Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone (1997), giving the ogre an appearance in a commercially-successful children’s book. She did little to deviate from Tolkien’s trolls, reinforcing the image of the creature as depicted in the elder author’s masterworks. Twenty-first-century film adaptations of Harry Potter and The Lord of the Rings, and finally, The Hobbit, broadened the opportunity to experience the horror of trolls, each based on the Norwegian original.

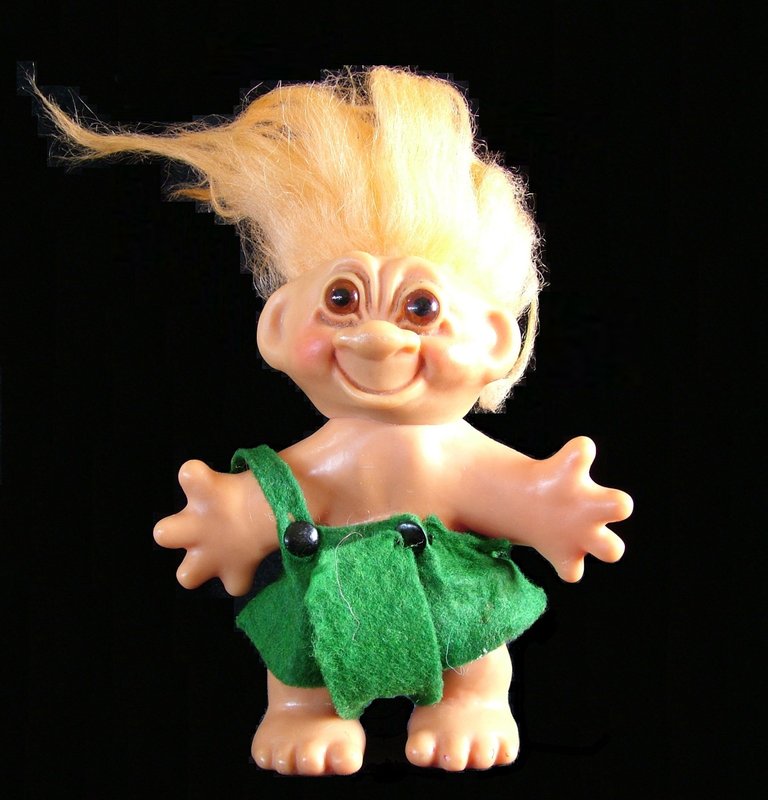

But this wasn't the only type of troll lurking in Scandinavia, and here's the trouble with trolls. In the early 1960s, a new type of troll came to the English-speaking world, this one from Denmark. Troll dolls became the rage. At the same time, something seemed very wrong with this tiny creatures who were ugly to the point of being cute. What did these trolls have to do with the monster lurking beneath the bridge?

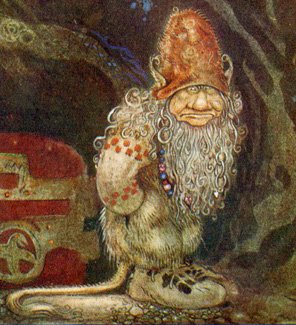

A novice to folklore may be surprised to learn that the Scandinavian troll tradition was varied and complex in its native land. For most of the century and a half since their arrival, trolls were of the Norwegian variety, but the Danish dolls hint at the diversity. Sweden completes the spectrum of possibilities with a rich spectrum of stories that describes a world filled with diverse types of trolls: the first illustration in this blog is in fact Swedish: in Sweden the trolls tend to be grotesque and somewhere between their Norwegian and Danish counterparts in size. In all of Scandinavia, people perceive these creatures as dangerous because they have supernatural powers and they are often a threat to humanity.

So, the trouble with trolls is that just when we think we understand what they are all about - based on one of the imports - we are confronted with yet another representative of the diversity of Scandinavia. The region, after all, covers a great deal of real estate, and people used the term "troll" to refer to supernatural beings that were generically similar, but diverse in specific attributes. Ever since 1859, the English-speaking world has tried to grapple with the conflicting images coming from Scandinavia, but despite our best efforts, the trouble with trolls is not likely to be resolved.

Just to make things clear here - some of this text was borrowed from a book I published - I don't want this blog to seem to be plagiarized. I deal with this in my book, "Trolls: From Scandinavia to Dam Dolls, Tolkien, and Harry Potter" (published in 2014, and reissued in 2017 with minor editorial changes).