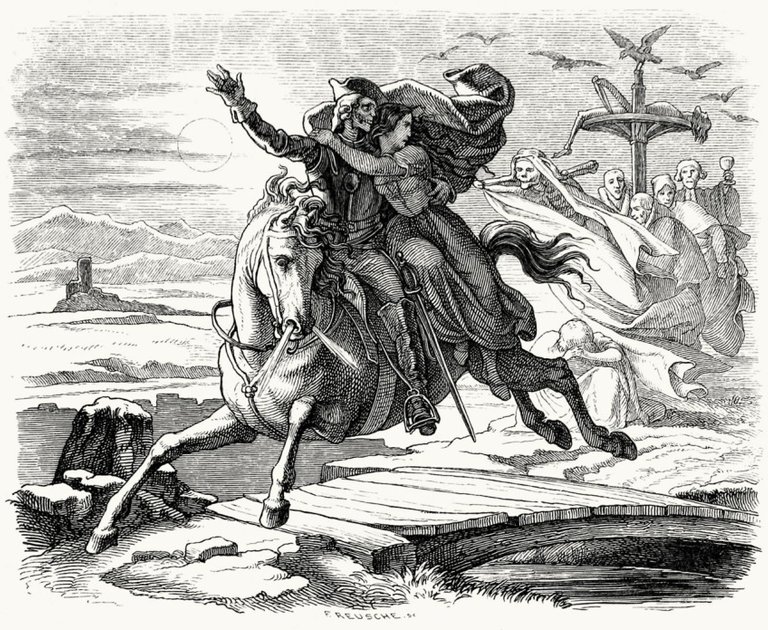

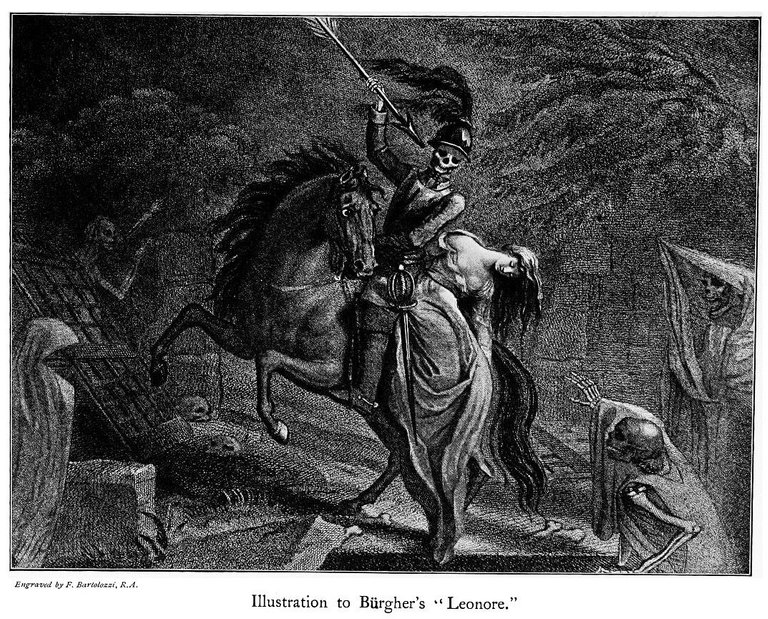

A widely-distributed story, common in Europe and represented in the folklore collections from Cornwall, draws on an array of popular beliefs and motifs. In most of Europe, the tale involved a devoted young couple separated by war. The man died, but his betrothed did not receive the news. One night, his spectre visits the woman and invites her to join him on his horse. It is not apparent that he is dead, so she accepts. They charge across the landscape, and near the end of their journey as dawn approaches, the woman realises that she is riding with the animated corpse of her lover. In most variants, she escapes, but she often dies shortly afterwards.

Gottfried August Bürger (1747-1794) made this story famous with his 1773 poem, ‘Lenore’. Within a decade after its publication, the German-language masterwork appeared in English translation, becoming an immediate sensation and apparently influencing Coleridge, Wordsworth, and other Romantic-Era British poets. Bürger’s publication was so influential that folklorists often refer to the tale simply as ‘The Lenore Legend’.

This story - sometimes told as a folktale and other times as a legend (to be believed) - was both widespread and old, influencing printed versions. It manifested in Britain and Ireland, and those forms give insight into its independence from various published forms. Irish variants share motifs with those from Cornwall, for example, demonstrating that an oral tradition influenced the written versions more than the other way around. The Cornish variants go a step further by illustrating an adaptation to the ocean: many examples have the couple escaping by boat to a watery grave, rather than by horse to a terrestrial destination. The influence of the ocean occurs in other stories found in the Cornish repertoire.

.jpg)

For what appears to be the earliest printed expression of this specific motif, one needs to reach back to eleventh-century Scandinavian literature. The medieval collection of verse, The Poetic Edda, includes the ‘Second Lay of Helgi the Hunding-Slayer’. This describes how Helgi, a dead hero, returns from the grave on a horse to beckon his beloved, Sigrún, for one last night of conjugal bliss. The document hints at the age of the motif, but it also suggests that initially, the story may have played out differently: Sigrún willingly enters Helgi’s burial mound to lie with him. The poem subsequently relates that the heroine ‘lived but a short while longer, for grief and sorrow.’ With this, the medieval text concurs with the conclusion of its more recent counterpart. This example suggests that for pre-Christian society, crossing the line into the realm of the dead for romance could be heroic. Nineteenth-century expressions of the story generally assert that no living person would want to enter the grave, even when it is the last resting place of a lover.

An excellent treatment of the Irish variants can be found in Ríonach Uí Ógaín and Anne O’Connor, ‘“Spor ar An gCois Is gan An Chos Ann”: A Study of “The Dead Lover’s Return” in Irish Tradition’, Béaloideas, 51 (1983) 126-44. Some of the text in this post borrows from my forthcoming book, The Folklore of Cornwall: The oral Tradition of a Celtic Nation (Exeter: University of Exeter Press, 2018).

I wonder how it is related to the Ukrainian folk tale of the “corpse bride”? The story is different, but shares similar thematic points (the marrying of a corpse).

This is a great question, to which there is no solid answer. Stories sometimes "flip" gender roles, so it is not impossible that they two could be historically/genetically related. On the other hand, they may be, simply, striking similar chords. Distinguishing the one from the other - particularly when dealing with close proximity - may be impossible.

I have wondered if Tale Type 313, which is behind Jason's abduction of Medea - and which is spread throughout Europe - is not behind the Celtic complex of stories that manifest in Diarmuid and Grainne, Tristan and Isolde, and Lancelot and Guinevere. In these stories, the woman often plays the dominant role, directing the king's hero to leave with her. Are these related to Type 313? Perhaps, or maybe they merely play with the same themes. My inclination is to see these as related. I don't know enough about the corpse bride to evaluate her relationship to the betrothed who dies in a distant land and then returns to the woman who promised to marry him. But that is a great question!