Nearly ten years after Truman came out, John Adams, a 751-page biography of the second President, came out - Adams, one of our more forgotten presidents, and yet, as becomes clear over the course of it, may have had one of the finest and most principled characters of any of the Founding Fathers.

I apologize in advance for the poor quality of the cover scan... the copy I am reading from is a library copy and there weren't any hi-resolution scans anywhere on the 'net.

Published in 2001, David McCullough's John Adams started life as a dual biography of Adams and Thomas Jefferson, who served as President back to back. He became, however, drawn increasingly to Adams. And no wonder: Jefferson as private, reserved individual, even in his letters, while Adams was happy to pour himself into his letters - and he wrote a lot of them!

Thus McCullough for six years worked on the biography, visiting the places Adams lived in and reading the books Adams read.

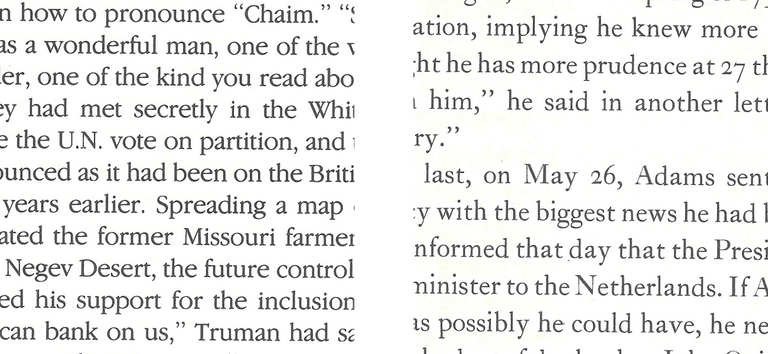

A strange complaint, but hear me out. Not only is the pagecount smaller than Truman was, the font is larger, the spacing between lines bigger, the margins of text and page edge larger. Allow me to show you the difference between Truman and John Adams text size and spacing, represented by a two-inch square selected randomly from one of the pages.

I adored the length and detail of Truman, and though John Adams is indeed lengthy and detailed, it is not as lengthy and detailed, which was slightly disappointing to me.

With that said, though, I understand how John Adams has now supplanted Truman as McCullough's defining work. John Adams, too, has gone on to win a Pulitzer. It was made into a television miniseries by HBO (though this miniseries had many historical inaccuracies).

That short length, which I criticized, undoubtedly has a part to play in this. The result is a book just as well-paced as Truman was, but, lacking the extensive length, it comes off as pacier. It makes for a quicker read. The typography, too, is easier on the eyes than in Truman, which, admittedly, is a minor detail.

John Adams quickly emerges as a man who, whatever his flaws, remained true to his opinions and to his writings. He decried slavery, and sure enough, the Adams' never owned one. (Unlike Jefferson, who actually slept with one of his and owned dozens.) Like characters in the best novels, he remains true to himself, whatever pains it may take him through.

And often there is the emotion of a novel to Adams' life. In a life so long, lived through such world-changing events and often playing pivotal roles in those same events, how could there not be? As part of the committee to secure French alliance, and then in the Netherlands, securing Dutch financial aid. As President during the volatile French Revolution.

It's a magnificent tale about one of our most storied Founding Fathers. This book, and the HBO miniseries, undoubtedly have done a great deal to bring to the public eye John Adams as a figure of surpassing importance - Washington, Jefferson, Madison, Hamilton, these are all familiar names, and this book served as an effort to raise Adams to the stature he deserves.

Some of my favorite parts? Adams' letters, of which he wrote a great deal to Jefferson, to his wife, to his sons, to his daughter, to Benjamin Rush. As much as I enjoyed Adams' Presidency, and his admirable keeping-of-the-peace between France and the U.S. despite Hamilton's desire for war (which, however popular it might've been, would have been disastrous), some of my favorite parts were during the Revolution, when Adams was in France.

My main critique is above - that of length. But the other minor critique I would make is that there is little on the subject of Adams' political writings - a couple are mentioned, but they are not really exposited at any length or detail.

Just as with Truman, McCullough's respect for and affection for his subject shines through. Jefferson emerges as a fascinating, steely figure - decrying slavery despite owning dozens, professing to abhor party politics even as he emerges as a masterful "closet politician," deeply intelligent, difficult to know or truly understand, and bizarrely fond of ship metaphors.

Does McCullough favor his subject too much? I don't know. With Truman, McCullough was accused by one publication of writing a long love letter to Truman. And though the book decidedly slants in Truman's favor, we nevertheless see many of Truman's faults.

With John Adams, it seemed to me, we get a figure at once too good and too human to be real. Adams, a founding father of stature equal to Jefferson, and yet never deified or lionized. He's too doggedly human: his sense of vanity (which he acknowledges) and his occasional brutal anger. And yet he was more consistent in his application of what he wrote: I will point out yet again, the Adamses never owned slaves. Only once, when caring for Jefferson's daughter, did they ever have a slave under their care.

What emerges is the fascinating portrait of a man who is too human to ever be deified or lionized like so many of his colleagues were (we will never seen an Adams musical) and yet also one truer to himself than perhaps any of his colleagues were.

So... what's next. The Asimov's issue continues to hang over my head like the spectre of death, as does F&SF Jul/Aug and Sep/Oct. Also on my reading pile is Glimmer Train nr. 83. I have Paul Auster's 4 3 2 1, Joe Hill's Strange Weather (a collection of four short novels), and Ted Chiang's The Lifecycle of Software Objects all from the library.

I have Dreamsongs Volume II, Ben Marcus' The Age of Wire and String, Andrew Shaffer's Hope Never Dies (which I actually have finished but still need to do a photoshoot of, we got a signed bookmark and a couple other goodies), and the first three books of The Expanse (of which I've been watching the television show).

Beyond that the library has the first four volumes of Robert Caro's The Years of Lyndon Johnson (the fifth still in-the-works) which I have been resisting checking out for weeks because I have so many other books already checked out from the Library.

So... what's next.

Hope Never Dies. Afterwards, it's anybody's guess!