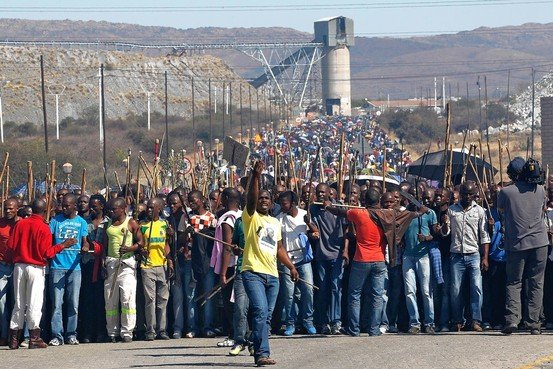

The view of images of the South African Police Service fighting battles with men armed traditional weapons is seen often on the independent news channels. This erupted into full scale violence in 2012 which ended with 36 mine workers from Marikana being killed by the police following a week in which 10 policemen and mine security personnel had been murdered.

Protesters from platinum mine (Wall Street Journal)

These images which were all too common in the late 1980’s and early 1990’s as South Africa narrowly avoided total civil war.

The national broadcaster (SABC) tends not to show images of protests using the excuse that often the presence of the media further fuels the violence. The same excuse was also used in the years prior to 1994 by the white Nationalist government. The difference this time however the Police are now on the side of the ANC and the State – and the men with the traditional weapons are rising up in protest of promises not kept. These promises were of a better life for all – and yet 22 years into democracy there has been very little real change for most of the people of South Africa.

AngloAmerican protesting workers (Reuters)

If we look at the mining industry it’s noted that South Africa is one of the World's and Africa's most important mining countries in terms of the variety and quantity of minerals produced.

It has the world's largest reserves of chrome, gold, vanadium, manganese and platinum group metals (PGM's). South Africa is the leading producer for nearly all of Africa's metals and minerals production apart from diamonds (Botswana and the DRC), uranium (Niger), copper and cobalt (Zambia and the DRC) and phosphates (Morocco). South Africa has a history of mineral exploitation that goes back thousands of years – the world’s oldest piece of art is considered to be a piece of haematite (iron ore) with a pattern etched into it which is thought to be 75 000 years old (found in Blombos Cave). San people used various minerals in creating their paints used for decorating their cave walls and recording events they were observing, and iron smelting in South Africa has been happening for over 1 500 years. Gold was extensively mined for local use but also later for trading and it would seem that Southern Africa was a significant supplier to the world economy between 600 and 1000 years ago. This gold would have been mined in the greenstone occurrences found in Mpumalanga as well as further north in Zimbabwe, and traded in the East African states of Mozambique, Kilwa and Zanzibar. Dhow sailing vessels would have then transported this gold to Middle East as well as Asia. Over 4 000 ancient gold mines have been identified in Southern Africa, and all the modern gold mines, except the deep level gold mines of the Witwatersrand, are on sites where the ancients first mined gold.

The early European settlers sent expeditions into the interior of South Africa looking for mineral deposits (notably copper with Simon vd Stel sending an exhibition into the Namaqualand region in the 1660’s), but the first commercial mining only commenced in the 1850’s. Discoveries of diamonds (1870’s), gold (1880’s) and later platinum however changed the fortunes of South Africa and it became the powerhouse in the world’s mining it is today. However all these new mines needed capital, lots of it, and that came from foreign investors. The name of “Anglo America” reflects this source of capital, and even today the major mining companies in South Africa have listings on stock exchanges in London, Toronto, New York and Sydney. The reality is that even though the mineral resources belong to the people of South Africa, we as a nation are still reliant on foreign investors to supply the capital needed to exploit this wealth.

The ANC recognised that the mining industry was not giving the benefits to the people of this country and already in The Freedom Charter of 1955 is written: “The national wealth of our country, the heritage of all South Africans, shall be restored to the people; the mineral wealth beneath the soil, the banks and monopoly industry shall be transferred to the ownership of the people as a whole”. This was followed up in the “Ready to Govern” document of 1992 : “The mineral wealth beneath the soil is the national heritage of all South Africans, including future generations. As a diminishing resource it should be used with due regard to socio-economic needs and environmental conservation. The ANC will, in consultation with unions and employers, introduce a mining strategy which will ... where appropriate; involve public ownership and joint ventures. Policies will be developed to integrate the mining industry with other sectors of the economy by encouraging mineral beneficiation and the creation of a world class mining and mineral processing capital goods industry.”

In May 2004, the Mineral and Petroleum Resources Development Act (MPRDA) was enforced, aimed at transforming South Africa's mineral rights regime, in which private ownership of mineral rights made way for a system of State custodianship. This should have been the instrument that the State was to use to ensure a more equitable distribution of the countries mineral wealth to the people. The MPRDA is essentially based on the principle of free mining, or “free entry” (FIFA system). Free mining includes:

- “a right of free access to lands in which the minerals are in public ownership,

- a right to take possession of them and acquire title by one’s own act of staking a claim, and

- a right to proceed to develop and mine the minerals discovered.”

The ANC is now asking if the FIFA system is to the benefit of South Africa?

It would appear that the actual mining companies benefiting from the minerals do so at the expense of the people of South Africa. The companies are however paying their income taxes as required as well as the newly imposed mining royalty’s tax (from 2010). They are complying with the provisions of the mining licence regarding social and labour requirements and thus feel that they have earned the right to make a fair profit considering their capital investment. Yet time after time we hear the local communities bemoaning the fact that they have no benefit of having a mine close to them.

At this point there are two things to consider – firstly, who is benefitting from the money paid from the company to the state, and secondly, who are the local communities. The income tax paid to the State goes into the State treasury, as does the money paid over as Royalties’ tax. This money is then distributed by the government as per their decisions regarding State expenditure. Does this benefit the local communities any more than any other community in the country? No – why should it? Why should a community 5km from a mine get preferential treatment to one 25km from a mine? So how do we define ‘local community’? Surely the ‘local community’ are the people employed at the mine – and these people can be sourced from geographical areas very far from the mine – in the case of the rock drill operators these men are mainly from the Eastern Cape and Lesotho. These men and their families benefit from the salary that the men bring home from having a job at the mine, and the community benefit by that money been spent in their businesses. That is to me how local communities benefit from the mines primarily. The mines provide skill training and education to their workers and their families as part of their social and labour plans – further benefiting and uplifting the community.

There is increased pressure on the government to nationalise the mines.

This was realised through the MPRDA of 2002, in line with the Freedom Charter, through the conversion of “old order” private rights to “new order” state rights. However, there have been challenges to this conversion on the basis that it is in effect a property expropriation under Section 25 of the Constitution. Further calls for nationalisation will just end up facing the same hurdles. New mining licences however are all issued under the provisions made in the MPRDA. The alternative to this is the establishment of a State Mining Company to exploit the mineral wealth directly. The question however is if this State Mining Company will be given the resources to compete with the international mining companies effectively, and become an efficient source of revenue for the State or just a burden being funded from other sources. Mining is hugely capital intensive, and it takes many years to bring a mine to a full production state. If the State Mining Company is expected to be a source of cash to prop up an ailing economy, it is doomed to failure.

So to conclude there appears to be a number of dilemmas facing the leadership of this country. How to distribute the wealth from the mining sector to the benefit of the people of South Africa? This cannot be achieved directly through the mining and sale of the commodities as the State does not have the resources available to invest in the mines. The secondary source of income (taxes and royalties) are being poorly spent by the government due to a corrupt and nepatalistic regime which is not providing the basic services as they promised to get the votes to get into power. The government has identified that job creation is a priority and yet now even people with jobs are dissatisfied as they are not earning enough to survive and improve their standard of living. The platinum price boom is over and the mines are in survival mode – just keeping things going till the prices increase again. There will be mine closures and further job losses, and the uncertainty facing potential investors in the South African mining industry is how safe their investments will be. Investors are looking for safer opportunities meaning the whole industry will begin to contract until it finally closes completely.

Where will that leave the people of South Africa and the mineral wealth deep under our feet?

The ANC feels that the State needs to have greater control over the mineral sector. How this control will improve the levels of service delivery is yet to be clarified as it would appear that even the basic needs of the people are not met even though there are sufficient funds in the budget to do so.

Chamber of Mines building at the University Witwatersrand, Johannesburg.

The author is a lecturer in Mine Financial Valuation and Mineral Resource Management and is reading for a PhD considering cut-off grade optimisation.